The Battle of Seven Pines near Richmond, VA in the spring of 1862 is one of the most overlooked yet significant fights of the Civil War. It was the closest major battle fought around Richmond, the Confederate capital, as well as the first fight between the Army of Northern Virginia and the Army of the Potomac. Each side suffered at least 5,000 casualties.

Why has Seven Pines, also known as Fair Oaks, not been given more attention by scholars? One reason is that the three-day fight ended in significant losses but no distinct winner. Another is that Seven Pines was dwarfed when compared to the series of fights called the Seven Days’ Battles that had 36,000 total casualties the following month and resulted in the end of Union General George McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign.

Furthermore, little of the Seven Pines battlefield has been preserved other than a few homes used as hospitals and roadside markers. The landmark Twin Houses are long gone. Today, the battle site has been replaced by the town of Sandston and a portion of the Richmond International Airport.

|

| The 85th PA is in Casey's Division in an exposed position when the fight began. Porter, Franklin and Sumner are all on the opposite side of the rushing Chickahominy River. |

Seven Pines nonetheless had great significance in the story of the 85th Pennsylvania. It was not only their first taste of the conflict (other than standing in formation during the Battle of Williamsburg a month earlier) but also for being the largest battle in which they ever participated.

Battle losses coupled with sicknesses that plagued McClellan’s army on their trek up the Virginia peninsula towards Richmond proved the months of May and June of 1862 to be the most devastating for the 85th in terms of combined deaths.

One of those in the 85th killed during the first day of the battle was 22-year old William Braden of Company B from Washington County. Braden’s company had just been replaced on the picket line by Company D when the Confederates launched their attack in the early afternoon of May 31. The 85th PA was soon a part of two retreats in the early hours of the battle from the area around the Twin Houses.

We have two first-person accounts from this part of the fight that state that Braden was shot and killed while trying to assist his wounded officer, Lieutenant George H. Hooker, from the field. Hooker survived his wound, was promoted to captain, and lived another 45 years.

|

| From the History of the 103rd Regiment PA Volunteers p. 174 |

Private Manaen Sharp, himself a member of Company B, recorded that, “Comrade Braden was helping to carry his wounded captain [Hooker, then a lieutenant] to save him from capture. Another comrade who was assisting, J.F. Speer of Canonsburg heard that sickening thud of a minie ball strike Comrade Braden, who said, ‘I am hit.’ He staggered to the road side….”

Manaen Sharp wrote his version of the incident in a brief a tract called “Amity in the Great American Conflict” in commemoration of Memorial Day in 1903 in which he chronicled the Civil War service of local residents. Sharp owned several furniture stores in Washington County and died in 1920 at the age of 82.

James F. Speer who completed carrying Hooker to safety following Braden’s death was later seriously wounded in the shoulder at the Battle of Second Deep Bottom in 1864 and survived. He returned home to Washington County and found work as a bricklayer and stone mason. Around the turn of the century he worked as a furniture salesman, perhaps in the employ of Manaen Sharp. Speer died in 1924 at the age of 82.

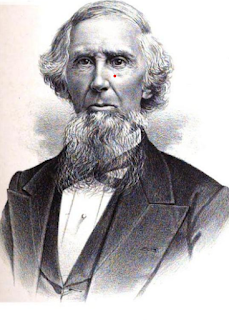

Lt. George H. Hooker

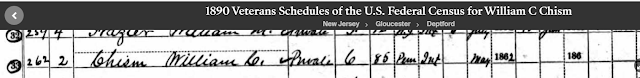

Since Braden’s body and those of hundreds of others on both sides were never recovered for individual burials, Nancy Braden, William’s widow, needed the written testimony of Captain Hooker as proof of her husband’s death in order to qualify for a widow’s pension. In 1865, Hooker wrote, “I hereby certify that Wm. Braden, a private of Company B 85th Pa. Vols., was shot while assisting me from the field at the Battle of Fair Oaks, Virginia on the 31st of May, 1862. He fell severely wounded and is supposed to have died from the effects of his wound.”

Hooker a native of the section of Virginia that became West Virginia during the war, was later promoted to captain and served as an adjutant on the staff of Colonel Joshua B. Howell. Hooker returned home to West Virginia following the war and farmed in Wayne County. He died in 1907 at the age of 66.

Besides his young wife, William Braden was survived by a one-year old son, George W. Braden. William Braden also served in Company B with his Nancy’s brother, brother-in-law, George Bigler.

Compared to the other hundred or so battlefield deaths in the 85th PA regiment during the war, the story of Braden’s battlefield demise is one with many details due to the accounts of Sharp and Hooker.

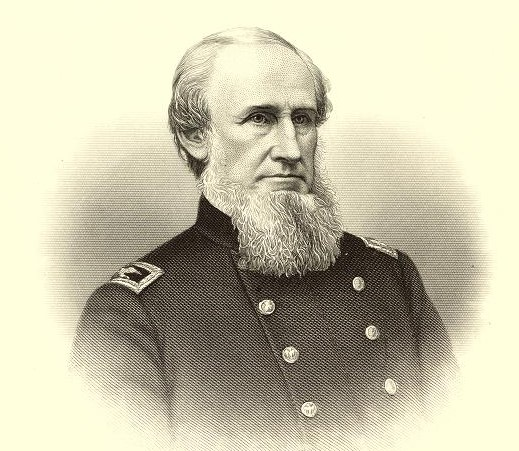

Now, because of the diligent work of Doug Carter, a former investigator with the Georgia Bureau of Investigation and a Civil war enthusiast, we can add to Braden’s story.

Carter has always had a fascination with the actions during the Civil War in his home state. His great grandfather, Jesse Taliaferro Carter, enlisted into the 3rd Georgia Reserves at age 17. He served as a guard at the Andersonville and Camp Lawton Prison Camps and later was wounded in the neck in December of 1864 in South Carolina

How did Doug Carter become involved in the story of the 85th PA? In his research, Carter, who is also a relative of former President Jimmy Carter, has identified the Georgia soldier who felled Braden at Seven Pines.

When I wrote my book about the 85th Pennsylvania regiment, called “Such Hard and Severe Service,” I relied heavily on primary sources; mainly the letters, diaries and memoirs of the men in the that regiment. In the early stages of the war, like for the Battle of Seven Pines, sources were relatively abundant for review. As the war dragged on however, more soldiers were killed, sent home with illnesses, or simply completed their three-year enlistments, which reduced the number of potential sources from about a thousand to 150 by the time of Lee’s surrender at Appomattox.

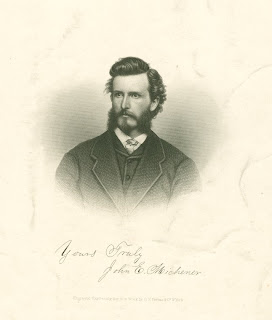

One recent Confederate source that came of light through the work of Mr. Carter was a letter written by Private Thomas Inglett of the 28th Georgia regiment.

|

| First page and cover of Thomas Inglett letter, June 10, 1862 Courtesy of Doug Carter |

It was Inglett who fired the shot that struck down Braden, a fact that Carter discovered 150 years later. It is a rare circumstance to be able to identify a dead soldier’s shooter so long after the event, if ever.

Ten days after the battle began, Inglett wrote a letter to his wife. “I killed one [Yankee] and got a letter out of his pocket that was wrote to him by his wife and I will send it to you and you can read it.”

The letter that Inglett lifted from Braden’s lifeless body was in fact not written by the Union soldier’s wife. Part of it was written by Israel Bigler and another portion was written by his13-year old Mary Bigler, whom Inglett thought was the dead soldier's wife. The letter never actually mentioned Braden’s surname.

|

| Researcher Doug Carter |

Carter purchased the Inglett letter in 2007, knowing that the Union letter in the envelope was an added bonus.

“I like researching,” said Carter. “I was a special agent with the G.B.I. investigating crimes and I like digging. I was determined to find out who this guy [Braden] was.”

Carter first realized the Union letter was four pages in length. He determined that most of the letter was written by Israel Bigler, a middle-aged farmer from Washington County to “Will” and “George.” The last page was written by “Mary Bigler” to “Will.” He next had transcribed the Bigler letter, a task not made easy by its blood-stained nature. Carter initially thought Will and George were both sons of Israel. Carter’s next step was to investigate the war services and lives of both Inglett and Braden to gain a wider knowledge of both men.

Inglett’s letter described his role at Seven Pines before he took the fatal shot against Braden. “I got my cap shot off of my head in the fight but I did not get hurt. Our poor boys fell all around me. James Price was killed with a canister shot before we got [with]in six hundred yards of the yankees. Sam Cawley was my file leader and he got shot down and the ball through [threw] blood all over my face and in my mouth, but they did not stop me for I was mad. Our regiment charged them twice and we made them run like dogs from their batteries.”

|

| Portion of letter that Inglett took from Braden's body. Courtesy of Doug Carter |

But Carter’s investigation of census records of the Israel Bigler household prior to the Civil War indicated that Bigler had no son named William. Braden, however, is listed in the 1860 federal census as a member of the Bigler household who was working as a farm laborer. Other family members were daughters Mary and Nancy who would soon marry William. From the 1850 census, Carter discovered that Israel Bigler did have a son named George Bigler, who was also a member of Company B. The census revealed that Israel Bigler also had a daughter named Nancy, who married William Braden in 1860.

Carter researched military records and found George Bigler and William Braden were in the same company of the 85th PA. By combing through the original 1913 history of the regiment, he determined that Bigler and Braden were both in Company B. He also discovered George had survived the war but that William was killed at Seven Pines. This was the key discovery that indicated that Braden was the owner of the letter confiscated by Inglett.

|

| Wikipedia Commons |

Thomas Inglett, meanwhile, grew up near Augusta, Georgia. He spent over three years in the Confederate army. He lost two fingers on his left hand due to a war wound during the Seven Days Battles a month after Seven Pines but recovered and continued to in his regiment

Inglett later suffered a leg wound at the First Battle of Darbytown Road on October 7, 1864 and was sent to a Richmond hospital. Ironically, the whole of the 85th PA fought in another battle at Darbytown Road just six days after Inglett was wounded. Most of the regiment went home the next day, having completed their three-year enlistments.

Tragically, three of Inglett’s infant daughters died while he was in the Confederate service. Inglett died in 1910 at the age of 71 and is buried in the Fort Eisenhower Cemetery in Richmond, Georgia.

Nearly a hundred of Inglett’s other Civil War letters can be found at the “Private Voices” website.

Combining the accounts of Inglett, Sharp and Hooker, several questions arise from the combination of the three stories.

The Israel Bigler letter had been written at least four months prior to Seven Pines. Why was Braden carrying it in on his person? It seems that he might have possessed a more recent letter at the time of his death.

Next, was Braden moving when he was shot? Inglett makes no mention in his letter that Braden was helping to carry away the wounded Hooker with another soldier. If Braden and Speer were on either side of Hooker helping to carry him away, did Inglett aim for the mass of the three men and happened to strike Braden or did he aim for Braden?

|

| Letter from Lt. Hooker in Nancy Braden's Pension File |

Or perhaps were the three Yankees stopped to rest when Braden fell? Sharp’s letter, which may have been directly related to him by Speer, seems to indicate that Braden was struck fatally but did not die instantly. Hooker wrote that he “presumed” that Braden died quickly from his wound. Did Speer decide that Braden was dead or mortally wounded when he staggered to the side of the road or was not going to survive, and thus carried on alone to help Hooker?

Inglett at first struck me as a bit cold-blooded in his rather casual mention to his wife that he lifted the letter from Braden’s lifeless body and chose to send it home to her as a souvenir.

However, when one reviews Inglett’s account of the fight prior to his targeting of Braden, the context makes his action a bit more understandable. Inglett mentioned the wounding of two of his comrades, one of whom splattered blood on his [Inglett’s] face and in his mouth. Inglett notes his own hat was shot from his head. He mentions that these events enraged him and encouraged him to press forward in the fight. This strikes me an a not uncommon reaction to being in a battle in which one’s friends have fallen around you.

Why was Braden’s body not recovered for burial? The only soldier of the approximately 25 men in the 85th PA who died from the battle who is buried in the Seven Pines National Cemetery, which was later situated in the approximate location on the 85th PA regiment’s camp, is Corporal Joseph Wilgus of Company B. That is only because Wilgus was wounded in the battle and died later. The field on which the 85th fought was soon overrun by Confederates. There was no chance at the end of the battle to return and recover bodies for burial. Another 85th PA soldier who died in the fight, Lieutenant James Reynolds of Company H. His body was left behind near the huge pile of firewood hear the Twin Houses, but his body was also not recovered for burial.

These questions will likely never be answered. However, due to Carter’s investigative diligence, we have a more complete story of the death of one soldier, William Braden of Washington County, who was one of thousands who died at Seven Pines.

Below are several depictions of the burial of soldiers after the Battle of Seven Pines

|

| Post-battle photo of the Twin Houses with the seven pine trees in the background. The foreground was said to have been used to bury 400 soldiers, perhaps including Braden. LOC |

|

| View of Seven Pines prior to the battle with the Twin Houses and 7 pine trees to the left. The camp of several regiments including the 85th PA can be seen in the background. LOC |

|

| Sketch of mass burials being conducted after the battle of Seven Pines. This view is from the direction of the first Confederate attack with the pine trees in front of the Twin Houses. LOC |