|

| Captain John E. Michener The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The |

My most recent post was about an escape attempt by Captain John E. Michener of the 85th Pennsylvania in 1864. It was told partly by Michener himself but mostly through the words of the Union prisoners with whom he attempted to flee. The post explored a letter to a newspaper that Michener wrote fifteen years after the escape in which he disputed a southerner's version of the use of dogs to track down slaves and escaped Union prisoners. The story of the escape and apprehension of Michener and his comrades was largely based on a postwar memoir by Captain John A. Kellogg of Wisconsin. Kellogg was one of the five Union officers who attempted to escape with Michener from a train bound from Georgia to Charleston, SC.

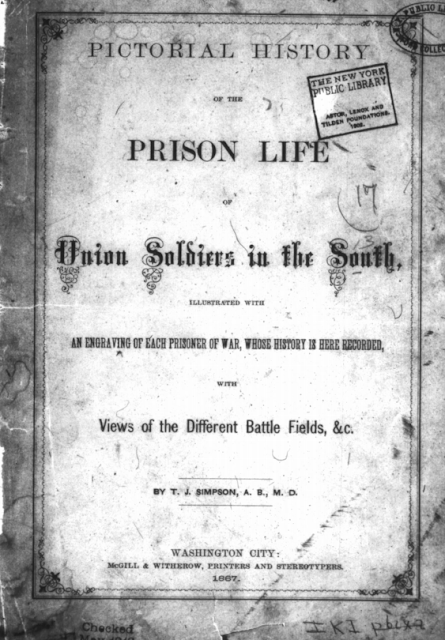

Michener had an account of his own war experiences published just after the Civil War, but I could not find a copy to review for this post. Thanks to George Thompson, the memoir has been found on microfilm at the New York Public Library. A copy has since been obtained and reviewed.

Based on the title of the Michener narrative, "Prison Life," I assumed that Michener's story would mainly be a first-person about his experiences in 1864. This includes the period in which he was captured on Whitemarsh Island near Savannah, GA to his release as part of a prisoner of war exchange ten months later. In the time in between those two events, Michener spent time in several Confederate prisons and tried to escape at least twice.

Surprisingly, just the last third of the 40-page chapter covered Michener's time in captivity. Furthermore, the Michener account ends while he was still in prison in Macon, GA. The daring escape attempt from the train bound for Charleston that was covered in my last blog was completely ignored in this treatment. It also omitted the last few months of his imprisonment as well as how he obtained his freedom. Why the overall work was entitled "Prison Life" is therefore a bit of a mystery.

However, what "Prison Life" does provide is a rich story of Michener's war experiences from 1861 to mid-1864. Although not written in the first person, the account certainly includes heretofore unknown details about Michener's service.

My next several posts will explore "Prison Life." In those posts, I intend to review what is known about the events concerning Michener and his regiment, the 85th Pennsylvania, and how Michener's memoir has enhanced our knowledge of these events. I will begin with the current post which will be an overview of Michener's brief tract.

Although at first disappointed at what was not written about in Michener's story, I now believe that these omissions are not that great of a loss. We have Captain John A. Kellogg's detailed review of the escape attempt and capture from the Charleston-bound train. We further know many of the details of Michener's time in a Charleston prison from a postwar letter that he wrote. The last few months of his time in prison was covered in several brief newspaper accounts from the period as well as the details of his exchange in the official records of the war.

The first two-thirds of "Prison Life" covers Michener's service in the war, from the Peninsula Campaign, to Suffolk, VA and finally to the fight at Whitemarsh where he and two others from the 85th Pennsylvania regiment were captured. Although we have several letters from Michener's family that give details of these events, "Prison Life" adds substantially to the story.

"Prison Life" appears to be intended as an opening chapter of a larger work to be written by T. J. Simpson. The title promised illustrations of various battlefields and implied there are more chapters to follow. But for some reason, the story of Michener seems to be the only one that reached publication. Michener and Simpson probably met in Washington, DC immediately after the war. During this period, Michener worked for the postal service and was involved in the creation of an organization for former Union prisoners.

It is curious as to why Michener simply did not pen the chapter in the first-person. Michener is virtually the sole source of Simpson's story. From letters that Michener wrote to his family as well as letters he penned to a few newspapers during the war, it is apparent that Michener could have been quite effective if he had provided a first-person account. Perhaps Simpson had better connections to get Michener's story into print.

Simpson seems to have used Michener's thoughts and words almost exclusively to write the chapter. One exception is a story from sutler James Clark (for whom Michener's brother Ezra worked) that is recounted. Furthermore, Simpson included some speech portions from other captured officers are used at the end of the piece. But otherwise, the remembrances seem to be from Michener alone.

Simpson writes in his introduction that, "...each one [story of a former Union prisoner] has some peculiarities connected with his history worthy of note, and many facts and incidents of an interesting and thrilling character which render the separate history of each one necessary to a correct and comprehensive view of the whole. The plan adopted, therefore, is to write the history of each one separately in a clear, concise and comprehensive manner."

Simpson went overboard in exalting Michener's accomplishments. It would have enhanced the chapter if Simpson had quoted other soldiers about Michener's deeds. A reader could easily assume that Simpson attempted to portray Michener as a super soldier, or even worse that Michener himself overinflated his experiences. Having read numerous other accounts by and about Michener, I do not believe it was Michener's idea to inflate his accomplishments.

During the Peninsula Campaign in Virginia in 1862, many men in the Union army became sick with various ailments including typhoid fever and other potentially deadly diseases. Simpson exalted Michener for assigning his black servant, likely a former slave, to care for the sick in the 85th Pennsylvania. By modern standards, Should Michener's so-called sacrifice in this instance be the object of such praise? Michener, wrote Simpson, "threw the coffee-cup, haversack, etc. over his shoulder, prepared his own food, washed his own clothes and cheerfully accepted the 'situation.'"

There is little doubt that Michener was extremely patriotic and highly regarded as an officer by the men in his regiment. As "Prison Life" showed, he was constantly put in charge of special assignments, a testament to his professionalism and reliability. Michener wrote several personal and public letters during the war denouncing antiwar sentiments and encouraging the citizenry to continue to fight to preserve the Union.

In late 1863, Michener wrote a letter to the Reporter and Tribune, a pro-war Republican newspaper in Washington, PA. Michener stated, "How do the Copperheads feel under the rebuke administered to them by the Union men on the 13th?...I believe your Southern sympathizers to be wickedly drunk to every feeling of loyalty or attachment to the United States Government. Their open treason, manifested by their cringing sympathy for the rebels; the vindictive spite with which they assail every friend of the Federal Government, and their opposition to a war prosecuted for the salvation and perpetuation of the Union is clear evidence of their infamous purposes, and wicked treason."

During his more than two years in the 85th Pennsylvania, Michener was often chosen to lead special assignments, such as in two incidents highlighted in Simpson's memoir; namely to shuttle prisoners and deserters aboard a schooner and being in charge of the barge that shuttled the 54th Massachusetts to Morris Island, SC for their historic charge against Fort Wagner.

Michener was also involved in leading men on special missions into battle, such as the assault on Battery Gregg on Morris Island and the attempt to capture a key bridge during the assault against Whitemarsh Island, GA where he was captured.

In this event, he made sure that all of his men had the chance to escape back to their transports, and was only captured because he was the last man to attempt to re-cross the bridge back to safety.

The best part of Michener's story is the account of his capture and the many privations suffered in prison. These evens as well as his time in the regiment prior to his capture will be explored in my next several posts in the order in which they occurred.