|

| LOC |

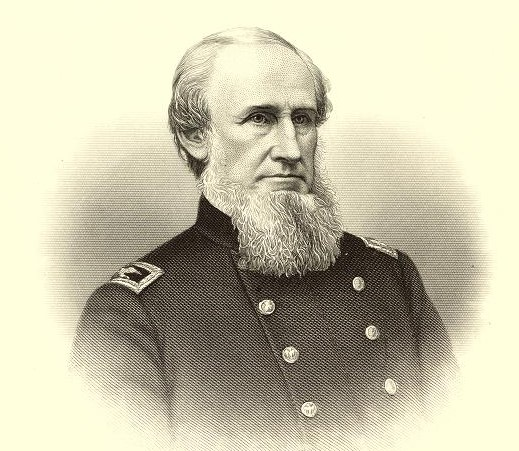

During the Civil War, Colonel Joshua Blackwood Howell had several personal assistants who attended to his needs in the field. Some were military personnel, like his aide, Lieutenant George A. Edson of the First Massachusetts Cavalry. Edson was with Howell in the summer of 1863 on Morris Island, near Charleston, South Carolina, when a Confederate shell scored a direct hit on the bombproof from which Howell was directing trench-digging operations. Howell was knocked unconscious and buried under a pile of rubble. Edson immediately pulled Howell out from under the debris and took him to a hospital, thus saving his life.

Another attendant known only as "Sam," an African-American who served as Howell's valet during the war. It is not known how Sam and Howell met; most likely, it was during the 1862 Peninsula Campaign in Virginia when the 85th regiment met many displaced former slaves. It was Sam who led a riderless horse during Howell's military funeral procession in September of 1864.

The following description of Howell's funeral is from Luther S. Dickey's official 1915 history of the 85th Pennsylvania.

"On the 17th, the Regiment was temporarily relieved from duty at Fort Morton, and escorted the remains of the Colonel from the brigade hospital to division headquarters. The ambulance that served as a hearse was immediately followed by 'Old Charley,' led by 'Sam,' a faithful negro servant of the deceased. 'Old Charley' the horse was then aged about ten years, and had accompanied the Regiment from Camp LaFayette, Uniontown, Penna., in November, 1861. He had been presented to Col. Howell while he was recruiting the Regiment by Jasper Thompson, Esq., of Uniontown, who had been a staunch friend and admirer of the Colonel...'Old Charley' [was not the] horse that caused the fatal mishap; [it was] a horse that had belonged to Capt. Loomis L. Langdon, 1st U.S. Artillery. On account of some infirmity of 'Charley,' the Colonel considered him unsafe to ride at night, and therefore had replaced him by the horse responsible for his death, and 'Sam' is the authority for the statement that this horse had a bad reputation as being vicious and tricky among the members of Capt. Langdon's battery, information he acquired after the fatal accident. However, Capt. Langdon's description of the horse is perhaps the most trustworthy; that 'it was exceedingly tender-mouthed.' Capt. Langdon was a warm friend and admirer of Col. Howell, and according to his statement, had presented the horse to the Colonel some time previous to the fatal occurrence, the latter having expressed a liking for the animal."

|

| Colonel Joshua B. Howell From L.S.Dickey's 1915 History of the 85th Pennsylvania |

A third personal attendant, the subject of this article, was William C. Chism. Chism was born around 1838 or 1839 and died in 1910 at the age of 70. The historical record of his life is quite sparse, but this article intends to explore what is known about Chism and speculate about the role he played in Howell's life.

The only reference to Chism in Dickey's history of the 85th Pennsylvania is found on page 308. The date is February 23, 1864. The regiment has just returned to Hilton Head, South Carolina from Whitemarsh Island, near Savannah Georgia. This one-day amphibious operation was to conviscate around 300 African American slaves who were building defensive positions for the Confederates in the area around Savannah.

The expedition, led by Howell and involving parts of several other regiments, started well enough. His two groups of assaulters swept through the island but were stopped by an unknown Confederate battery that had just been built on the other side of a bridge to Oatland Island. The 85th PA became pinned down and the Confederates maintained the bridge as a possible avenue for re-enforcements.

|

| Whitemarsh Island February 22, 1864 Map Courtesy of Craig Swain |

Howell's forces were forced to scurry back to their transports. No one in Howell's unit was killed, athough three men (Captain John E. Michener, Corporal James Bailey and Private Eli Shellenberger) were captured.

This reference to Chism in Dickey's regimental history picks up the story once the men returned to Hilton Head the next day.

"The Regiment disembarked and arrived in camp at Hilton Head at 1 a.m.; the men were immediately dismissed and were permitted to rest in camp the entire day; it was discovered that the Colonel's cook, William Chism, known in camp as 'Billy the Cook,' was missing, left on Whitemarsh Island."

The loss of Chism through probable capture or possible desertion is curious and leads to a series of questions to which the author could find no answers.

2. If Chism were captured that day, what was he doing off the transport Mayflower, Howell's flagship? There doesn't appear to be any reason for him to disembark or not stay close to the ship. Howell stayed either on the boat or close to the shore during the operation. Chism was not listed as having been with Michener and the others when they were captured, so if he were in fact taken prisoner, it had to have been in a separate incident.

3. Did Chism desert to the enemy? This seems unlikely. Chism seems to have been a lifelong resident of the North with no known ties to the Confederacy. Even if he did desert, why would be abandon a somethat cushy job of cooking Howell's meals?

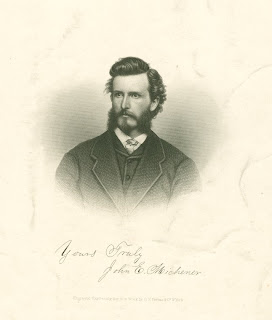

It should also be mentioned that in 1867, the aforementioned Captain John E. Michener, one of the three soldiers from the 85th Pennsylvania captured on White Marsh Island, wrote a brief but detailed treatise (along with author T.J. Simpson) of his war experiences called "Prison Life." Michener wrote of his own capture along with Bailey and Shellenberger on Whitemarsh Island and their subsequent moves to prisoner-of-war camps. Michener made no mention of Chism.

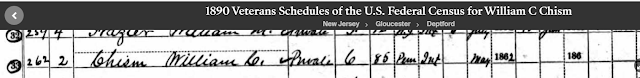

There is no other found government reference to Chism's life until the 1890 Veterans Schedule, a special census of Civil War soldiers. Chism, around 50 at the time, is listed as being a member of Company C of the 85th Pennsylvania. This came from Chism himself, who may have been passing himself off as a mustered-in soldier. But no other roster of regimental members has Chism listed as being a soldier of the regiment. Of course if Chism travelled with the regiment for two years and was captured during a military engagement, he probably felt he had the right to feel he was a legitimate member of the regiment.

The 1890 Veteran's Schedule states that Chism joined the regiment in May of 1862. Although there is no record of Chism's enlistment, this could be true. Again, this was during the Peninsula Campaign as "Sam" had probably done. Chism, who was white, was therefore in Virginia for an unknown reason. Howell and Chism could also have first crossed paths in western Pennsylvania during training camp, or in Washington, D.C. where the regiment was stationed for four months.

The Veteran Schedule has two other interesting notations. One is that although it is stated that Chism "mustered in" to the regiment in May of 1862, there is no muster-out date listed, only that Chism's regimental records are under the heading of "papers lost." This notation is not unheard of in the Veterans Schedule. Several other former soldiers in 1890 did not have documentation, usually due to memory issues or perhaps a fire that destroyed personal records in the 25 years since the war ended.

In Chism's case, however, it may be that he had no documentation to start with, due to his apparent role as a non-military personal assistant. Although Chism was with Howell during many battles, he likely told the examiner that he lost his papers when such papers never actually existed.

The second interesting notation in the Veterans Schedule regarding Chism is listed as a side note. This was usually written on the line on the form in which the examiner listed any Civil War maladies that came from the soldier's war service, such as an amputation, heart troubles, etc.

For Chism, the doctor simply wrote, "nine months in prison."

This claim again came from Chism. It would suggest, in a very tenuous way, that he indeed was captured on Whitemarsh Island in 1864. However, I could find no record of his release anywhere among Union POW records. This may mean that he had convinced the Confederates that he was not a soldier and became more of a political prisoner. He may also have been used for his specialty -- preparing meals -- for Confederate officers or privates the way captured Union doctors were put to use by southern armies when they were confined.

Here is an article that appeared in a Gloucester County, New Jersey newspaper in 1885 that has some interesting claims regarding Chism's relationship with Colonel Howell.

The 85th Pennsylvania did indeed fight at Kinston, North Carolina in December of 1862. It was during a two-week foray called the Goldsboro Expedition that a Union strike force of 12,000 soldiers attempted to disrupt the Confederate supply chain into Virginia. But if Chism were captured on Whitemarsh Island and held for nine months, he would have been released around November of 1864. Colonel Howell died as the result of a fall from his horse two months earlier in September of 1864. This raises several more questions.1. If Chism were accurate about he period of confinement, he was not with Howell when he died in September of 1864. How would he know, as the article stated, that the Colonel used the North Carolina law book as his pillow "until the time of his death."?

2. If Chism were in prison when Howell died, how would he have acquired the law book from among Howell's personal possessions, assuming they were sent back to his adopted home in Uniontown, PA to his family or to his boyhood home in New Jersey with his body for burial?

3. Would Colonel Howell have really used a law book to rest his head upon at night for over two years during the war? It seems a book would have made an exceptionally hard surface to try to sleep on.

In reviewing census records, it was unusually difficult to otherwise track Chism's life. It does not appear that Chism ever married or had children. There were many William Chism's among the census records of the late 1800's, although most lived in the South. Chism was only found in the 1890 Veterans Schedule because of the reference to the 85th PA.

A decade later, according to the 1900 census, Chism may have been employed as a coachman for soap manufacturer Emma M. Thomson and her family in Atlantic City, New Jersey. This census, however, states that Chism and his parents were all born in Pennsylvania. The next year, he seems to appear as a gardener in a city directory for Atlantic City.

Chism does appear ten years later in the 1910 U.S. Census, This was also the year of his death. Chism at this time lived in Deptford, Gloucester County, New Jersey, which is only two miles from where Howell was raised in Woodbury. Howell also was buried in Woodbury. .

In the 1910 census, it is stated both Chism and his parents were born in New Jersey. This connection could be a clue regarding Chism's employment by Howell during the war.

[There is also a hint in the 1860 federal census that Howell and Chism may have met at the start of the war. This census, lists a 23-year old carpenter from Pittsburgh (who was born in Pennsylvania) named William Chism. At least one company of men trained in the Pittsburgh area before joining the 85th Pennsylvania at their base camp in Uniontown, Fayette County. This could be the connection between Chism and the 85th regiment.]

Under occupation in the 1910 census, it is stated that that elderly Chism was a military veteran living on his own and was a "private pensioner." Could Chism have been granted a personal endowment by the Howell family for his loyal service during the Civil War? Did the Howell family employ Chism after the war, since he at least in his final years lived near the Howell family in New Jersey?

The author was looking forward to answering some of these questions when he began this enquiry. But his investigation has only led to more questions. If Chism were a loyal servant who was captured by the Confederates while serving his mentor during the Civil War and was rewarded for it with a "personal pension" from the Howell family after the war, it would have been nice to find confirmation of such a relationship.

Here is a picture of Chism's headstone in the Almonesson United Methodist Church Cemetery in Gloucester County, New Jersey.

No comments:

Post a Comment