|

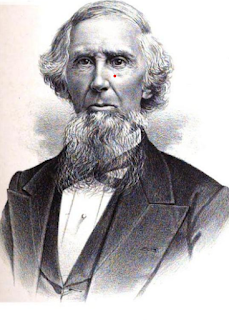

| Lieutenant John W. Acheson The Progessive Men of the Commonwealth of PA, Vol. 1, 1900, p. 269 |

Lieutenant John Wishart Acheson was an ambitious, intelligent and courageous soldier. He survived the war but died shortly afterwards at the young age of 34. Nonetheless, the accomplishments of Acheson and his brothers as a members of various Union regiments are noteworthy.

Judge Acheson was born in Philadelphia, but his parents hailed from Washington County. Young A.W. Acheson went to college in western Pennsylvania and remained in Washington, PA ("Little Washington") until his death over seven decades later.

Just before passing away in 1890, Judge Acheson recalled a memory from his childhood. Mr. Acheson remembered from nearly 80 years beforehand, "One of my earliest recollections was when school took a recess to see the soldiers pass through town on their return from the War of 1812. Of that band of children which gathered on the pavement, I am probably the only one now living. The company which passed was the 'Ten Mile Rangers.' A black horse, which had belonged to one of their officers who was killed at Niagara Falls [also known as Lundy's Lane], was led in front. That must of have been in the fall of 1814." [Washington Semi-Weekly Reporter, July 12, 1890, page 6]

Military service would become a very important in the lives of Judge Acheson's children. Judge Acheson himself did not have a military career. He was admitted to the bar in 1832. He served four terms as district attorney before becoming a regional county judge in 1866 and spent 23 years on the bench. Politically he began as a Democrat, although he switched to the Republican Party in the years just prior to the Civil War.

Besides John, his eldest child, Judge Acheson had four other sons who served in the Union army during the Civil War. John Acheson was very ambitious for promotion during his three-plus years in the army. He knew the best way to advance was to show coolness, fortitude and leadership in battle, which he often displayed. He also seemed to have the political connections that would assure his furtherance in military.

However, John became frustrated that his path to higher rank was proceeding slowly or maybe was blocked. This may have been due to political reasons, as Colonel Joshua B. Howell of the 85th PA was a member of a different political party. Acheson was a strong supporter of Howell early in the war but the relationship soured and John eventually transferred out. John's rise may also have been blocked for health reasons, which will be explored below.

However, John Acheson's patriotism, capability and bravery were above question. He came from one of the elite families of Little Washington, but he and his brothers displayed a sense of noblesse oblige regarding the war. John proved to be an effective leader while under fire. He was wounded three times, a testament to his commitment to the Union cause and to those who served under him.

Following the war, John's life was cut short due to various addictions, including alcohol. Perhaps these dependencies came from his war service and difficulty in overcoming his physical wounds. Some soldiers also turned to the bottle out of boredom or due to the horrors of the battlefield. John's death came in 1872. This was ironic because his father was a strong advocate of the temperance movement throughout his political career.

John Acheson graduated from Washington College (later Washington and Jefferson University) in 1857 and was a language instructor for several years before studying to become a lawyer. But he quickly enlisted a few days after Fort Sumter fell in 1861 into the 12th PA infantry for three months along with his brother, David. Their company was commanded by Colonel Norton McGiffin, who would later become the lieutenant colonel of the 85th PA. The 12th regiment, a three-month unit, saw no action at the First Battle of Bull Run in July of 1861. They were instead tasked to guard a railroad near York, Pennsylvania before disbanding.

While two brothers, David and Alexander "Sandie," soon joined the 140th PA, John enlisted for three years into Company A of the 85th Pennsylvania.

David Acheson became the captain of Company C of the 140th PA. On the second day of fighting at the Battle of Gettysburg, Captain Acheson was killed near Stoney Hill when engaged against a South Carolina regiment. His remains were later recovered after the battle and buried near the Weikert Farm. Near his gravesite, his company placed a small boulder and carved his initials, "D.A" into the stone along with "140th P.V." David Acheson was 22 years old. His body was eventually brought home and buried in Little Washington.

| |

History of the 140th Regiment Pennsylvania, R.L. Stewart, 1912, P.124-5 |

David Acheson was succeeded as the captain of Company C by his younger brother, Sandy. Sandy Acheson was shot in the face (but survived) at the Battle of Spotsylvania in 1864.

|

| Sandy Acheson History of the 140th PA |

A fourth brother, Marcus "Mark" Acheson, was born in 1844 and enlisted into the 58th PA infantry in 1863, one day before his brother David was killed at Gettysburg. Marcus spent a few weeks in this three-month regiment and was mustered out in mid-August.

|

| Joseph M. Acheson Progressive Men of PA |

A fifth son, Joseph, enlisted into Knapp's Battery in 1864 at the age of 16. He contracted malaria during his four months of service that troubled him for the rest of his life. He died at the age of 38 in Fairfield, Iowa.

|

| Ernest Acheson https://www.govtrack.us/congress/members/ernest_acheson/400681 |

In 1986, librarian and local historian Jane Fulcher (1916-2005) published a collection of letters entitled "Family Letters in a Civil War Century." In her book, Ms. Fulcher, Ernest Acheson's granddaughter, included about 20 letters written by John Acheson during the war.

[Note: All of the quotations below are from "Family Letters In a Civil War Century: Achesons, Wilsons, Brownsons, Wisharts and Others of Washington, Pa.", Jane Fulcher, Avella, PA, 1986.]

Nine days after the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter, John Acheson heeded President Lincoln's call for 75,000 volunteers and enlisted into the 12th PA. From Pittsburgh, Acheson wrote, "I cannot describe to you the excitement that exists here...the people are wild, crazy...The military spirit of our state seems thoroughly aroused. Companies of volunteers are continually passing through the city en route to Harrisburg." [Page 299]

After his brief enlistment in the 12th PA expired, John joined Company A of the 85th PA. Part of the reason may have been Colonel Howell, who organized the 85th, was a personal friend of Judge Acheson, which John Acheson probably hoped would benefit his pathway to promotion.

With his younger brother David already a captain of his own company, John yearned to be an officer as well. He wrote, "I am willing and anxious to join the army if I can secure a position. I do not believe it to be my duty to enter the service for three years as a private, nor will I do it." [Page 305]

|

| Professor Thaddeus Lowe in His Balloon Virginia Peninsula, 1862 Library of Congress |

Despite his reservations, it does appear John Acheson joined the 85th regiment as a private. Within the next six months, though, he won a series of promotions and became a 1st lieutenant in August of 1862. He had distinguished himself at the Battle of Seven Pines in Virginia, where he led his company and received two wounds in the wrist and leg.

In mid-1862, he asked his father to intervene to help him secure a commission as the permanent captain of Company A due to the medical resignation of Harvey Vankirk. "I think if anyone has claims on the Colonel for the captaincy of Company A, I have. I have shared its dangers and privations and was always with them no matter what duty was to be performed. Col. Howell knows all of this, and for this reason, he promised the captaincy should be mine. His conduct in the matter is very strange." [Page 311] John Acheson was not named captain of Company A; the position instead went to William W. Kerr.

A year later, David Acheson was killed and another younger brother, Sandie was voted to become the captain of David's old company in the 140th PA. John, still a lieutenant, wrote the following to his father in early 1864 from Hilton Head Island in South Carolina. Once an ardent supporter of his colonel, Joshua B. Howell, John Acheson became more and more incensed at his commanding officer for preventing his advancement in the 85th.

"I would like to get a transfer to General [Absalom] Baird in order to show Colonel Howell that my success as an officer did not depend on his toadies. This is all the triumph I want....I can serve the balance of my term as First Lieutenant cheerfully, but I do not like to see men who have little or no qualification outstrip me."

"I want you to fully understand that your former friendship with Colonel Howell will not weigh a feather with him. He is a weak, vain, ambitious man, and insensible to everything that does not tend directly to further his prospects for a Brigadier Generalship...I long for the opportunity to show him that however regardless he may be to my interests, I have friends at home who are just as able as he to secure my position." [Page 313]

|

| Execution Harper's Weekly |

While stationed in South Carolina, John earned the ire of General Quincy Gillmore, the commander of the Department of the South, for a clerical error during the court-martial of three soldiers from the 10th Connecticut who were slated for execution due to desertion. Two of the men were hanged, but a third stayed alive because his name was misspelled on the official record of the court matial. Gillmore was most upset and blamed Acheson for the oversight.

Acheson was perhaps a bit nonchalant in the performance of this duty because he had already accepted a position with General Absalom Baird, a division commander in the western theater who happened to hail from Little Washington. With this unit, Acheson would participate in Sherman's March to the Sea. From Jonesboro, Georgia, in 1864, where he was wounded, John wrote, "General Baird was in the thickest of the melee. This end of the Confederacy is about caved in. Atlanta is ours. I will embrace the first opportunity to write you a long letter." [Page 317]

Once Sherman's Army captured Savannah, Georgia on the Atlantic Ocean, they headed due north through South Carolina [see map below]. Two weeks before the end of the war, John wrote, "On the South Carolina side [of Savannah], huge torpedoes [land mines] had been placed in the mud. Little injury was done by them. Two or three soldiers had their legs blown off, but that was about all. But how silly was this conduct of the chivalrous citizens of the Palmetto State! Our soldiers swore revenge and every man supplied himself with an extra bunch of matches. Day after day while marching along the road past burning dwellings, barns and out-houses, the line of march of other columns might be discerned by the dense masses of black smoke darkening the heavens on every side. South Carolina, which hitherto has suffered so little from the war, has been terribly punished for her folly and crime." [Page 320] |

| David A. Scott, A School History of the U.S., NYC, Am. Book Co., 1884, p.371 |

Only three days before his death, his brother Sandie wrote to their mother, "I have received a letter from Sadie [Sandie's wife] stating that John is seriously ill...If you think it best, and he is willing to come [home], he must make one vow before he starts and that is 'never to touch tobacco again.' If he'll do that, the alcoholic tendency can be controlled and the opium will not be so harmful or may be broken off. But if he persists in using tobacco, he will be liable to the day of his death to fits of depression (a result of the tobacco) which he cannot control and which will compel him to resort to stimulants. His only safety lies in quitting tobacco." [Page 332]

John Acheson is buried in the Washington Cemetery in Little Washington, PA.

|

| https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/157037892/john-wishart-acheson |